The day after my father died in 2017, I came in to teach my regularly scheduled classes at PVA. My supervisor was more than willing to give me the day off, but I thought the diversion of teaching would be better than sitting at home all day before I could make the trip home. I was right. The story we were reading for the student presentation in the advanced class was Stephen King’s “Strawberry Spring” and generated a diverting discussion. That semester another student ended up selecting “The Lawnmower Man” from the same Stephen King collection, Night Shift (1977), for their presentation, commenting that the movie adaptation of this story was not worth speaking of. This month marks the release of an adaptation of another story from this old collection, “The Boogeyman,” which, on an episode of The Kingcast, its director Rob Savage said its writers Scott Beck and Bryan Woods pitched as both an adaptation of and a sequel to the original story. I’d say it’s worth speaking of.

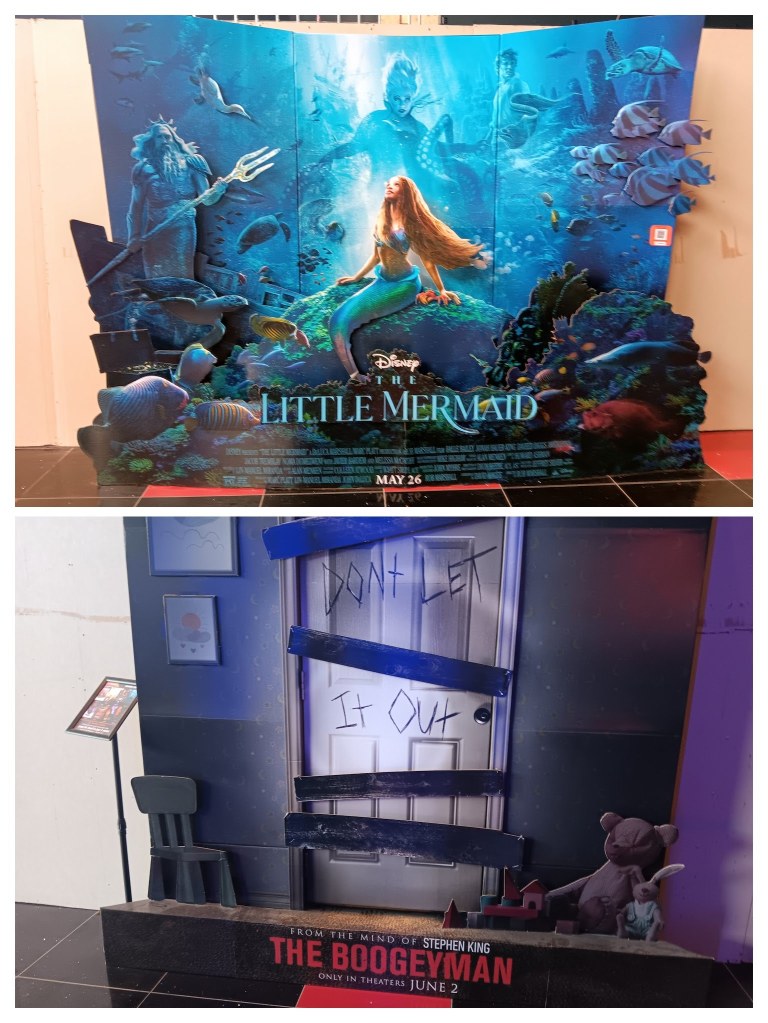

Since Disney has acquired the studio 20th Century Fox, this horror movie is technically a Disney production. Even if I hadn’t been actively researching connections between Stephen King and Disney, the fact that the remake of The Little Mermaid was also just released might have led me to notice a similarity between these two adaptations–new additions to the source material rendering a dead mother critical to the narrative, albeit to varying degrees.

“The Boogeyman” is a story so short that a film adaptation would have to expand it, which this one does by exploring the dynamics of the family of the therapist in the original who supplies the narrative frame: the entire story is narrated to him by a patient. In the movie, the family dynamics pivot on a dead mother, the therapist’s wife, who has died in a car accident shortly before this patient comes in to tell him how the boogeyman has killed all of his children. As the boogeyman starts to terrorize the therapist’s younger daughter, his older daughter starts attempting to summon the spirit of the dead mother. While there are numerous unequivocal cues that the monster is “real” within the context of the film and not just a figment of any of the characters’ imaginations, the cue that the dead mother’s spirit is present and helps intervene in the climactic battle with the monster cements this monster as an effective allegory for grief.

In The Boogeyman a recurring dress of the dead mother’s also embodies her symbolic presence, not unlike how a dress in The Little Mermaid is used as a visual cue to emphasize the loss of Ariel’s human form when she turns back into a mermaid.

The function of guilt is also an interesting overlap between these texts. In The Boogeyman, the father-therapist suggests that his patient’s claim of the Boogeyman killing his children is a projection of his guilt for killing the children himself, and so it takes him awhile to come around and believe his daughters that the Boogeyman is real. This aspect of his character is intertwined with his (ironic for a therapist) inability to talk about his dead wife with his daughters, again linking the monster’s terror to processing the mother’s death. In The Little Mermaid, the function of guilt is more indirect, with one critic claiming the film is targeting an audience of “guilt-ridden millennials.” What are they guilty about?

Like so many of Disney’s live-action remakes, this movie is for the now-middle aged millennial women who grew up watching (and loving) the 1989 original — only to become scandalised, as adults, by their heterocentrism, their whiteness, their phobias and isms.

Kat Rosenfeld, “The Little Mermaid is Disney propaganda,” UnHerd (June 5, 2023).

(If The Boogeyman is about processing guilt as well as grief, and is technically a Disney movie, can it be read as processing the guilt of loving older problematic Disney movies?)

The erasure of the mother might also be part of this guilt, which brings us to Disney’s dead mother trope. One comprehensive study of the representation of family structures in animated Disney movies found that nearly half represented single-parent households, which the company apparently considers an effective plot device:

Our results indicated that close to half (41.3%) of Disney animated films depicted a single parent family. Don Hahn, an executive producer for some of the most well-known Disney animated films (including Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King), provided commentary for this storyline selection:

“I never talk about this, but I will. One reason is practical because the movies are 80 or 90 min long, and Disney films are about growing up. They’re about that day in your life when you have to accept responsibility. Simba ran away from home but had to come back. In shorthand, it’s much quicker to have characters grow up when you bump off their parents. Bambi’s mother gets killed, so he has to grow up. Belle only has a father, but he gets lost, so she has to step into that position. It’s a story shorthand.” (Radloff 2014)

Jessica D. Zurcher, Sarah M. Webb and Tom Robinson, “The Portrayal of Families across Generations in Disney Animated Films,” Social Sciences (Basel), vol. 7, no. 3 (2018), 11 (boldface mine).

While at times the single parent in these households is the mother, more often it’s the father, because the mother is dead:

When the mother is alive and present, she is as good a mother as she possibly can be. However, she is powerless, for whatever reason, to really help her child, thus forcing the child to save him- or herself. Most often, however, she is not only dead, she is never even mentioned. Fathers are a little luckier in Disney. They are rarely killed, and whereas only a handful of Disney characters have mothers, many more – nineteen out of thirty-nine – have fathers. Granted, where there are fathers, they are often just as incapable of protecting their offspring as are the mothers…

Amy M. Davis, Good Girls and Wicked Witches: Women in Disney’s Feature Animation (2006), 103.

In keeping with the tactic of “corrections” of some of the problematic aspects of its source material in Disney’s live remakes, some of these films have “corrected” the dead or absent mother not by bringing her back to life, but by explaining what happened to her, often in ways that then become critical to the overall narrative. So it’s not the death or absence itself that’s corrected so much as the utter lack of explanation for it that, when taken as a pattern, seems to render the figure of the mother utterly irrelevant, which is ironic in light of the technically critical nature of any mother figure–if the characters weren’t born, none of the events in the movie could happen.

So, to sum up some of Disney’s mother-related corrections:

In Beauty and the Beast (2017), we learn that Belle’s mother died from plague in a new twist on the magic that the Beast in his isolated castle has at his fingertips–or rather, his claw tips. The nature of this magic was narratively troublesome to Linda Woolverton, the screenwriter of the ’91 animated version (groundbreaking for being the first animated movie to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Picture, and the first Disney animated feature to be penned by a woman):

Woolverton also questioned a change that saw the Beast come and go from his castle via a magic mirror. “The castle is supposed to be impenetrable,” she says. “After that, the mythology didn’t work for me.”

From here.

In The Little Mermaid update, we learn that Ariel’s father Triton hates humans so much, and is thus dead set against Ariel’s most burning desire, because humans were responsible for the death of Ariel’s mother, which is set up by the live film opening with the men on Eric’s ship attempting to harpoon what they think is a mermaid (which they’re doing so because they believe an aspect of mermaid mythology that was not prominent in the original–that mermaids will lure and kill men with their siren song). One critic also reads Ursula the villainous sea-witch as “maternal,” and if Ursula’s death constitutes the narrative’s climax, this interpretation renders the climax itself a “matricide,” or death of the mother:

Ariel sacrifices her connection to the feminine in the matricide of Ursula, the only other strong female character in the film. Eventually, Ariel achieves access by participating with Eric in the slaughtering of Ursula, relegating her and that which she signifies to silence and absence. Ursula is reassigned to the position of the repressed that keeps the system functioning. Embedded in gynophobic imagery, Ursula is a revolting, grotesque image of the smothering maternal figure (Trites 1990/91). Of course, within Disney’s patriarchal ideology, any woman with power has to be represented as a castrating bitch.

Laura Sells, “‘Where Do the Mermaids Stand?’: Voice and Body in The Little Mermaid,” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, ed. Elizabeth Bell (1995), 181.

Eric also gets an adopted Black mother in the update (in addition to a dead father), one whose race is supposed to be a correction of a lack of diversity but in turn introduces the problem of rendering a picture of racial harmony that erases the history of slavery attendant to its apparent 18th-century Caribbean setting.

In the Pinocchio (1940) update released last year, Geppetto is rendered a widow and Pinocchio a re-creation of his dead son. No explanation appears to be provided for how either of them died.

In the Peter Pan (1953) update released this year, Peter Pan & Wendy, we learn that Captain Hook and Peter Pan used to be friends until Hook, then going by James, wanted to leave Neverland because he missed his mother. But he ended up abducted by pirates on his way out and never saw her again.

The original Dumbo (1941) provides an interesting exception to Disney main characters lacking mothers: Dumbo has no father and no explanation as to where he might be–despite his mother being referred to as Mrs. Jumbo. The mother’s absence, if not her literal death, becomes a critical aspect of the plot when she’s chained up as a “mad elephant” after defending Dumbo from mockery and physical assault, leaving Dumbo to fend for himself. Since Dumbo is one of the shortest “full-length” animated features, barely over an hour, the 2019 remake entails almost an entire narrative overhaul, with the addition of new–human–characters whose conflict is constituted by–you guessed it–a dead mother, in this case one who’s died of influenza, since the film is set in 1919. This time setting engenders a father figure who lost his arm in the war and returning does not know how to manage the parental duties that were his wife’s domain, as emphasized to an obnoxious degree by the equally obnoxious daughter character (and equally obnoxious actress) saying un-subtle things like “‘Mom would have done something.'”

The King of Disney

Disney’s influence on Stephen King can be traced along many lines, but the original Dumbo and Peter Pan would seem to be especially prominent Disney texts for him. In his fantasy magnum opus Dark Tower series, King inserts himself as a character who is writing the story, and when some of the main characters are about to meet this King-character in book 6 out of 7 of the series, Song of Susannah (2004), one character “sensed it: … the gathering power. … Eddie found himself thinking of Tinkerbell’s magic dust and Dumbo’s magic feather.” This would seem to figure King as possessing a “magic” on par with Disney’s, but on closer examination, the functions of the magic dust and magic feather, while similar–both are related to the ability to fly and to a prominent character who does not get any spoken dialog–they are markedly different. King invokes the function of Dumbo’s magic feather in a nonfiction discussion of writing:

Dumbo got airborne with the help of a magic feather; you may feel the urge to grasp a passive verb or one of those nasty adverbs for the same reason. Just remember before you do that Dumbo didn’t need the feather; the magic was in him.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

Dumbo turns out not to need the magic feather to fly: put another way, the feather is not actually magic. Tinkerbell’s magic dust, on the other hand, is necessary for the ability to fly–and thus is, in the context of its narrative, actually magic. I’ve started to think of these two types of Disney magic as representative of a bifurcation/duality King himself has articulated in his 1980 essay “On Becoming a Brand Name”–King the brand, and King the writer. As the former, King has the power to promote other writers in what is the symbolic equivalent of sprinkling Tinkerbell’s magic dust on them, making their books figuratively “fly” in the marketplace. If you recall the bold gold color associated with this magic dust in the animated version, King’s magic dust in this sense is akin to the Midas touch: if he endorses you as a writer, he turns your book into gold. I’ve seen this happen with my fiction teacher from college, Justin Cronin, who got King’s Midas touch magic dust sprinkled on his Passage trilogy (which I’ve discussed here). Cronin’s first book since this trilogy, The Ferryman, just came out, promoted, again, by King. You can ascertain the significance of King’s magic dust in the number of times King’s name comes up in interviews with Cronin like this local Houston show. (King himself called in to Good Morning America during Cronin’s appearance there to promote the first Passage book back in 2010.)

Another bifurcation/duality reflected in the concepts of brand versus writer exists in the academic concepts clarified by the scholar Alan Bryman of “Disneyization,” which describes Disney’s branding influence (primarily through their theme parks), versus “Disneyfication,” which describes Disney’s narrative influence. The dead mother/dead parent trope would be an aspect of the latter, which is used in the film Escape from Tomorrow (2013):

His paternal loss places the young boy in the pantheon of children featured in Disney films who lack one or both parents and learn how to navigate the world for themselves.

Aviva Briefel, “Mickey Horror: Escape from Tomorrow and the Gothic Attack on Disney,” Film Quarterly , Vol. 68, No. 4 (Summer 2015), 42.

This article posits that this movie’s filmmaker Randy “Moore relies on long-familiar images of what Barbara Creed terms the ‘monstrous-feminine’ to convey … a gothic account of the parks’ cooption by a dangerous female consumerism that nullifies male resistance or escape” (36-37). Moore is quoted to support this reading:

“[Visitors to Disney parks] want to revert back to the womb, to the safety they had as a child. It’s the ultimate nanny state.”

Aviva Briefel, “Mickey Horror: Escape from Tomorrow and the Gothic Attack on Disney,” Film Quarterly , Vol. 68, No. 4 (Summer 2015), 37.

And a footnote further notes:

As Max Axelrod suggests, Disney’s stepmothers and fairy godmothers are connected in their roles as nonbiological substitutes for real (and often absent) mothers (31). Max Axelrod, “Beauties and Their Beasts & Other Motherless Tales from the Wonderful World of Walt Disney,” in The Emperor’s Old Groove: Decolonizing Disney’s Magic Kingdom, ed. Brenda Ayres (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), 31.

Aviva Briefel, “Mickey Horror: Escape from Tomorrow and the Gothic Attack on Disney,” Film Quarterly , Vol. 68, No. 4 (Summer 2015), 43.

In its critique of Disney (or more specifically, of “Disneyization”), this film essentially inverts Disney’s dead-mother trope by rendering the Disney parks as a killer mother (hence the dead parent being the father). A horror movie set at Disney World, Escape from Tomorrow looks at Disney through a Stephen-King lens, an inverted version of what this post is doing in looking at Stephen King through a Disney lens.

There are other prominent Disney aspects that have influenced King apart from types of magic. In response to the question of why he writes horror, he has claimed that “‘[t]he first movie I ever saw was a horror movie. It was Bambi’.” This is due to the forest fire sequence as well as to what is probably Disney’s most iconic dead mother, Bambi’s shot by the unseen hunter.

If the narrative use of dead mothers could be read as a sign of Disney’s influence on King (as a narrative influence, this would be a way King has been “Disneyfied”), this merges with the two Disney magic types in the recent Gwendy’s Button Box trilogy, which makes prominent use of a magic feather and Peter Pan references. The name of the title character, Gwendy, is:

“A combination. My father wanted a Gwendolyn—that was his granny’s name—and my mom wanted a Wendy, like in Peter Pan. So they compromised.”

Stephen King and Richard Chizmar, Gwendy’s Button Box (2017).

As you can see, King co-wrote this book, handing it off to Chizmar to finish when he “ran out of gas”; having started the story, King is responsible for the title character’s partially Disney-derived name. Book 2 of the Gwendy trilogy, Gwendy’s Magic Feather (2019), Chizmar wrote by himself in what amounts to another example of the power of the King Midas touch magic dust. King’s name appears twice on the book’s cover despite the fact that he did not co-write this one:

The narrative further develops connections to past King characters and events associated with what Chizmar himself calls the “sacred ground” of the fictional King setting of Castle Rock. The story seems to depend on these connections to garner reader interest instead of developing a compelling narrative in its own right. The pacing is completely off, as evidenced by the late introduction of the titular object at the book’s halfway point. This clunkiness is compounded by the fact that the late introduction places Gwendy’s procuring of the feather at a point in time not long before the events in the first book, which never once mentions this feather, undermining that the feather is as significant to Gwendy as this book’s title would imply. The book seems more a collection of subplots with no main plot–rather it’s more of a plod through a too detailed accounting of Gwendy’s daily activities.

King’s penchant for sentimentality is another marker of Disney’s influence on him, but Chizmar’s use of it goes too far for my taste in Gwendy’s father’s articulation of the feather’s meaning:

Gwendy thinks about her father’s words from earlier: “We all poked fun at you about that feather, Gwen, but you didn’t care. You believed. That’s what mattered then, and that’s what matters now: you’ve always been a believer. That beautiful heart of yours has led you down some unexpected roads, but your faith—in yourself, in others, in the world around you—has always guided you. That’s what that magic feather of yours stands for.”

Richard Chizmar, Gwendy’s Magic Feather (2019).

Despite the book never explicitly mentioning Dumbo, the description of this function aligns with its non-magical function in that narrative. This places it in contradistinction to the function of the titular object from the first book, the button box, which, like Tinkerbell’s dust, is actually magical. Chizmar’s description of the feather’s origin comes closer to referencing Peter Pan in deriving from “an Indian chief who used to live around here. He was also a medicine man, a very powerful one,” which resonates with both the stereotypical treatment of Native Americans as “the red man” in Disney’s Peter Pan King’s associations of stereotypes with small-minded Mainers (the feather’s “Indian chief” origin is shown to be a made-up lie by the kid who sells the feather to Gwendy, essentially painting this con-man kid as a version of Disney himself). Chizmar also has Gwendy think of the co-worker she considers her mentor “as Tinkerbell, the wand-waving, miniature flying guardian angel of her childhood.”

In the 2019 Dumbo, the obnoxious daughter character with the dead mother wears a key around her neck that serves a similar psychological placebo function as the non-magical feather:

“My momma told me there’d be times when my life seemed locked behind a door. So, she gave me this key, that her momma gave her. And said whenever I have that feeling, imagine that door…and just turn the key.”

Dumbo (2019).

This heavy-handed object, planted early with the above dialog that would violate Robert Boswell’s use of narrative spandrels discussed here, returns in a later critical moment that updates the development when Dumbo learns he doesn’t need the feather to fly, after his feather burns up in a fire:

“Dumbo, remember this? From my momma? I can unlock any door. And you can, too. But I don’t need

Dumbo (2019).

this key to do it. And you don’t need the feather. Come on.”

And she throws the key into the same burning tent where Dumbo’s magic feather ignited, festooned with the posters advertising Dumbo’s performance with his picture and a single word: “BELIEVE.”

Gwendy’s Magic Feather‘s underdeveloped chronic-tension conflict purports to revolve around Gwendy’s struggle with the question of whether her successes are the result of her own abilities or the magic of the button box. This chronic tension is brought to a head by the equally underdeveloped acute tension conflict of a serial killer operating in Castle Rock whose identity Gwendy uncovers via the unequivocally magical ability of a psychic button-box-induced vision when she touches him, after which point he is apprehended quickly and easily, and with Gwendy not even present–a rushed narrative climax with absolutely no tension. In the resolution, the bestower of the magical button box comes to collect it and resolves her chronic tension issue in what manifests a total narrative contradiction:

“Your life is indeed your own. The stories you’ve chosen to tell, the people you’ve chosen to fight for, the lives you’ve touched …” He waves his hand through the air in front of his face. “All your own doing. Not the button box’s. You have always been special, Gwendy Peterson, from the day you were born.”

Gwendy forgets to breathe for a moment. She feels an enormous weight crumble from atop her shoulders, from around her heart. “Thank you,” she manages, voice trembling.

Richard Chizmar, Gwendy’s Magic Feather (2019).

In addition to plainly bad writing at the sentence level, this reinforcement of what the not-actually-magic titular magic feather stands for completely violates what was shown by the critical and clearly magical role of the button box in the (anti)climax. This false conclusion that Gwendy can do it all on her own without the magic of the button box reads like an allegory for Chizmar trying to convince himself that the success of this book would be the product of his own abilities as a writer and not have anything to do with assistance from King’s magic dust branding, when that assistance is not only clearly everywhere (the cover promotion, King characters and settings, the continuation of a narrative King himself started), but all the book has going for it.

The serial killer that should be the main conflict but is not properly developed as such is nicknamed the “Tooth Fairy” (due to his penchant for pulling the teeth of his victims), which would thematically connect to the theme of the power of “belief” in the feather’s symbolism that Gwendy’s father articulates. The “tooth fairy” as a traditional concept is not real, just like the magic of the feather is not real, nor is this serial killer magical/supernatural, even though the psychic visions Gwendy has that lead to his capture are. The use of teeth in representing whether something magical/supernatural is at play is also in The Boogeyman, when the older daughter tries to pull the younger daughter’s loose tooth the same way their dead mother had, by tying the ends of floss around the tooth and a closet doorknob and then shutting the door. Not only does the door shut by itself, later, when everyone is asleep, we see the tooth get pulled by an invisible force toward the closet door and up the jamb. The tooth returns in a freaky sequence when the older daughter smokes some old pot she found that belonged to the mother (using an intermittently functioning lighter that belonged to the mother as well) and starts coughing, then pulls something out of her throat: the string of floss with the tooth at the end of it. At first I wondered if this indicated the older daughter was the Boogeyman. But ultimately it reinforces that the boogeyman is grief for the dead mother, which is further reinforced by the mother’s lighter subsequently indicating her spirit’s material presence when its flame bends at an impossible perpendicular angle in the same climactic sequence the lighter is used to burn up the Boogeyman (and, inadvertently, the dress of the dead mother’s that the older daughter’s wearing has been articulated as indicating her inability to “move on”). Thus the narrative’s network of object use lines up nicely, twined around the themes of grief and belief, as when the father refuses to believe the older daughter that the Boogeyman is real because she smells like pot when she tries to tell him. A big part of the rising action escalates around belief: first the youngest daughter believes the monster is real, then the older daughter, and, finally, the father.

There’s also another mother character in The Boogeyman, the mother of the children the initial patient tells the therapist-father were killed by the Boogeyman. This mother is not dead in the original King story, but her role in the movie is expanded. Another change is that this patient desperately wants the father-therapist to believe his Boogeyman claims, while in the story he insists repeatedly that he knows the therapist won’t believe him. It’s this insistence about belief–or lack thereof–that constitutes the climactic reversal in the story:

“Mr. Billings, there is a great deal to talk about,” Dr. Harper said after a pause. “I believe we can remove some of the guilt you’ve been carrying, but first you have to want to get rid of it.”

“Don’t you believe I do?” Billings cried, removing his arm from his eyes. They were red, raw, wounded.

Stephen King, “The Boogeyman,” Night Shift (1977) (boldface mine).

In addition to tooth (fairy) invocations related to questions of belief, the mother of this patient’s dead children offers another oblique connection between The Boogeyman adaptation and the Gwendy trilogy–the actress who plays her, Marin Ireland, is the audiobook narrator for Gwendy‘s final installment, in which Gwendy’s dead mother will become narratively critical.

If Gwendy’s first name evinces the presence of Disney via a character in Peter Pan, so does her (phallic) last name: Peterson, implicitly privileging the patrilineal. The primacy of the father in this narrative could alternately be read as undermined or supported by a subplot that threatens the death of the mother in Gwendy’s Magic Feather: when Gwendy’s mother’s cancer seems to return, she takes Gwendy’s magic feather with her when she goes in for tests, while Gwendy simultaneously consumes a chocolate dispensed by the magical button box–and then the tests reveal the mother is cancer-free. As though attempting to correct the falseness of Book 2’s conclusion that Gwendy has done everything in her life on her own, Book 3, Gwendy’s Final Task (2022), which King returns to co-write, repeatedly emphasizes Gwendy’s belief that it was the magical button box that saved her mother, not the non-magical feather. Yet by the time Book 3 starts, her mother has since died. This death will be critical to the trilogy’s Disney-tinged conclusion, hinging on a flashback so saccharine and so long it threatens to choke the reader: while looking through a telescope at the stars, Gwendy asks her mother what she believes about the afterlife. While King is hardly innocent of the sin of being overly sentimental, I’d like to believe Chizmar is mostly responsible for this sequence, mainly due to the poor pacing of its disproportionate length. But there is another narrative sin here that’s a recurrence from early enough in Book 1 it seems King might well have written it: Gwendy’s mother being referred to as “Mrs. Peterson” from what should be Gwendy’s close-third-person point of view, which should thus describe this figure as “her mother.” But other parts of this sequence also violate that close-third perspective by going into Mrs. Peterson’s perspective, a sin against the positioning of this sequence in Gwendy’s memory.

Gwendy returns to this memory at the series’ end when, improbable as it sounds, she is floating in space toward a death she has chosen over living through the continued mental deterioration of Alzheimer’s, a price she’s paying for her use of the magical button box. When first experiencing the lack of gravity in space near the beginning of Book 3:

She unbuckles the harness and floats upward from the narrow mattress. Just like Tinkerbell, she thinks in a moment of pure amazement.

Stephen King & Richard Chizmar, Gwendy’s Final Task (2022).

The final lines of the book, minus the epilogue after her death in which her father is given a message Gwendy left him, merge the dead mother’s conception of the afterlife with Peter Pan’s directions to Neverland:

…she sees a single shining star. It’s Scorpius, and heaven lies beyond it. All of heaven.

“Second star to the right,” Gwendy says with her final breath. “And straight on… straight on til…”

Her eyes close. The Pocket Rocket with the button box in its belly drives onward into the cosmos, as it will for the next ten thousand years, towing its spacesuited figure behind.

“Straight on til morning.”

Stephen King & Richard Chizmar, Gwendy’s Final Task (2022).

This conclusion invoking the Disney narrative with the actually magical “magic dust” symbolic of King’s brand further undermines the power of the actually non-magical “magic feather,” thus reinforcing that this series reinforces the power of King’s brand rather than that of Chizmar’s writing (the worse Chizmar’s writing is, the stronger it shows King’s brand to be…).

In the Company of Parents

Starting in the ’80s, Disney begat subsidiary companies producing texts that audiences likely did not realize were made by Disney, rendering itself a “parent” company. (Creating its own subsidiary companies is distinct from acquiring pre-existing companies as it would in the ’90s, in which capacity Disney would be more of a “step-parent” company.) Analyzing films both officially stamped with the “Disney” label and those by its children companies, Lynda Haas argues that “of the three hundred and some films Disney has produced in the last sixty years, mothers, when represented at all, are more stereotypically (and ideologically) drawn than any other character” (197). Haas zeroes in on three films in which Disney more prominently represented mothers, focalizing them as main characters:

To her contention that mothers must be symbolized in ways that are “other of the other,” Irigaray adds that “the relationship between mother/daughter, daughter/mother constitutes an extremely explosive kernel in our societies. To think it, to change it, amounts to undermining the patriarchal order” (Irigaray 1991, 86). It is not surprising, then, that Disney has made only three films that feature mother/ daughter relationships: Touchstone’s The Good Mother (1988) and Stella (1990), and Hollywood Pictures’ The Joy Luck Club (1993). The sheer fact that the mother is in the spotlight contests filmic norms. The Good Mother and Stella offer the obligatory sentimentalized versions of motherhood; neither mother is able to self-define herself, and both films focus on the necessary sacrifice/punishment that culture dictates to mothers who would be subjects in their own right. However, from within the Disney house–the place where in an insidious and seemingly apolitical way, stereotypes are usually entrenched and reproduced–comes The Joy Luck Club, perhaps the best example produced thus far to show that mothers can be represented in such a way as to resist hegemonic expectations and reclaim a feminine standpoint.

Lynda Haas, “‘Eighty-Six the Mother‘: Murder, Matricide, and Good Mothers,” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, ed. Elizabeth Bell (1995), 197.

Haas identifies The Good Mother as “an adaptation of Sue Miller’s morally didactic novel bearing the same title” (198), seeming to implicate the movie’s source material as equally lacking. It happens that in Boswell’s spandrel essay, another novel by Sue Miller, For Love, is offered up as an example of what not to do in an example of a “fake scene” that is fake because it is “without story consequence,” serving to develop a metaphor without doing so within the context of an event that’s actually relevant to the overall plot, and thus “[t]he narrative deflates because the rules of compression have been ignored” (57).

The Joy Luck Club opens with the invocation of a feather whose symbolism seems more prominent than its plot significance, since it does not return after its mention in the narrative’s opening anecdote:

The film opens resistantly: a disembodied female voice-over tells the story of a Chinese woman who buys a special swan; it was once a duck, but “stretched its neck in hopes of becoming a goose, and now look–it is too beautiful to eat.” Then the woman travels across an ocean many Ii wide, to America, where she hopes to have a daughter who will “be too full to swallow any sorrow. She will know my meaning, because I will give her this swan–a creature that became more than what was hoped for.” However, when she arrives, the customs officials take her swan and she is left with only a feather. She keeps it until the day when she can tell her daughter, in perfect American English, “This feather may look worthless, but it comes from afar and carries with it all my good intentions.“

Lynda Haas, “‘Eighty-Six the Mother‘: Murder, Matricide, and Good Mothers,” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, ed. Elizabeth Bell (1995), 204-05 (boldface mine).

This feather’s seeming violation of Boswell’s narrative principles might reveal the shortcomings of the Western patriarchal principles themselves rather than the shortcomings of Tan’s narrative; Boswell sets up his explanation of his meaning of “narrative spandrels” with a belabored explanation of how “adaptation” works in the context of evolution that includes the incorrectness of believing that the adaptation of the giraffe’s long neck is a result of stretching it in the manner of Tan’s duck above (48).

It also happens that Stephen King is friends with Amy Tan and that she occupies a prominent place in his book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000). In the book’s “First Foreword” King asks Tan:

…if there was any one question she was never asked during the Q-and-A that follows almost every writer’s talk—that question you never get to answer when you’re standing in front of a group of author-struck fans and pretending you don’t put your pants on one leg at a time like everyone else. Amy paused, thinking it over very carefully, and then said: “No one ever asks about the language.”

I owe an immense debt of gratitude to her for saying that.

…

Amy was right: nobody ever asks about the language. They ask the DeLillos and the Updikes and the Styrons, but they don’t ask popular novelists. Yet many of us proles also care about the language, in our humble way, and care passionately about the art and craft of telling stories on paper. What follows is an attempt to put down, briefly and simply, how I came to the craft, what I know about it now, and how it’s done. It’s about the day job; it’s about the language. This book is dedicated to Amy Tan, who told me in a very simple and direct way that it was okay to write it.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

Amidst this expression of anxiety about his own brand, King also mentions here that he and Tan are in “a rock and-roll band composed mostly of writers. The Rock Bottom Remainders,” a band that at times includes the creator of The Simpsons, Matt Groening–an implicit explanation as to why King and Tan both appeared in the same Simpsons episode where the family is forced by Lisa to attend a book fair. The joke Tan gets is relevant to the literary treatment of mothers, when Lisa addresses her during the exact type of Q&A King mentions above (though not to ask a question):

Lisa: Ms. Tan, I loved The Joy Luck Club. It really showed me how the mother-daughter bond can triumph over adversity.

Amy Tan: No. That’s not what I meant at all. You couldn’t have gotten it more wrong.

Lisa: But-

Amy Tan: Please, just sit down. I’m embarrassed for both of us.

The Simpsons 12.3, “Insane Clown Poppy” (November 12, 2000).

(While Marge, the Simpsons matriarch, is the one who interacts with King, this episode’s main premise revolves around fatherhood, as Krusty the Clown discovers he has a daughter he never knew about.)

If King listened to Tan about the language, he doesn’t seem to have listened to her about the significance of mothers, but rather to Disney. This is not to say Disney and King did not personally have significant son-mother bonds. King’s household would have fit in Disney’s single-parent household representations, as he was raised by his mother Ruth after his father abandoned the family when he was two; as detailed in On Writing, she supported and encouraged his writing and was the first to pay him for it. Ruth died of cancer when King was 26, shortly before his first novel Carrie was published–though she did, on her deathbed, get to see an advance copy of this novel in which the main character kills her own mother. Walt Disney’s mother Flora’s death seems possibly even more traumatic. After the success of his company’s first full-length animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) cementing the dead-mother/evil-stepmother formula:

Walt wanted to buy his parents Flora and Elias Disney a home near the Disney Studio in Burbank, California. After Flora complained about the gas furnace, Disney had repairmen sent to the home, but unfortunately, the problem was not resolved. Flora ended up dying of asphyxiation in the home Walt bought for her — which became a tragedy Walt would have to carry with him for the rest of his life.

From here.

In keeping with this confluence, some other examples of King invoking the seemingly Disney-influenced dead mother would be:

In his most recent novel Fairy Tale (2022), the opening chapter details the main character Charlie’s mother’s death and how it sends his father into a spiral of alcoholism; this will in turn become critical to Charlie glomming onto a pseudo father figure who turns out to have a portal to a fairy-tale world in his backyard.

In Joyland (2013), the primary timeline is the year King’s mother died, 1973, and the main setting is a theme park that defines itself in contrast to Disney’s overly slick corporate parks. The main character Devin’s mother is dead from the outset, though this seems less critical to the narrative than Devin’s girlfriend Wendy dumping him, which causes him to take a semester off from college and extend his summer employment at the Joyland park, where it turns out a serial killer is operating. (If Devin can, like Gwendy in Gwendy’s Magic Feather, uncover the killer’s identity, maybe he will find his own in turn and thus no longer be a symbolic lost boy in a symbolic Neverland.)

In The Plant (1982-85/2000), a curious experimental serial novel that King never actually finished (more on that here), Carlos, the character who sends the evil titular plant to Zenith House, the publishing firm who rejected his manuscript, is said to derive powers “‘from his mother, who wasn’t an idiot…except in her blind love for her son, which finally got her killed,'” while Riddley, the Zenith House employee who comes into possession of the plant, has to leave the office for his own mother’s funeral. During Riddley’s absence, the plant grows at a supernaturally accelerated rate until it takes over his closet-office space. At home for the funeral, Riddley, who is Black, has a falling out with his family members due to their stealing their dead mother’s effects, leading him to accept the white coworkers that he had previously disdained as a surrogate family who will try to capitalize on the plant’s supernatural powers together to overthrow their parent company, Apex Corporation.

The Plant‘s connections between corporate and traditional families offers another Disney link beyond the Disney brand’s bread and butter deriving from its family appeal. In the 2019 Dumbo, the villain, V.A. Vandevere, is a corporate titan with an uncanny resemblance to Walt Disney in running a theme park named “Dreamland.” He lures Max, the owner of the ragtag circus Dumbo is a part of, into the Dreamland fold by promising Max and his troupe “‘a home. … Join me and my family.'” But once they join, he lays them off: “‘Max, the contract says that I’d hire them. It never stipulated for how long. So, get your little band of low-rent freaks out of here.'” As one review points out:

Just as Vandevere feels like a modern echo of Walt Disney, Dreamland recalls Disneyland. Dumbo debuts a week after Disney finalized its merger with Fox, which got Disney its very own performing elephant — the Fantastic Four and X-Men franchises. As expected, the newly merged entity promptly announced redundancy layoffs. It’s strangely appropriate that after “merging” Dreamland with the Medici Bros. Circus to get his hands on the spectacular flying elephant, Vandevere attempts to fire the circus’ original performers, while placing Max in a figurehead, leadership role at the company. Vandevere is the film’s villain, but does Disney see the irony?

Kendra James, “Disney’s new Dumbo is a garish CGI mess,” The Verge (March 29, 2019).

King and Disney are iconic narrative-based brands that reinforce patriarchy like the beams that hold up King’s Dark Tower, which functions as the literal and figurative center of his literary universe. In the same aforementioned Dark Tower sequence in which the character Eddie associates the two types of Disney magic with King, Eddie also likens the Dark Tower’s main character Roland to King’s father. In book 4 of the series, Wizard and Glass (1997), Roland kills his own mother with his father’s guns, tricked into thinking his mother is a witch due to his mother’s reflection appearing as the witch (not unlike Ursula’s reflection in The Little Mermaid when she’s disguised as human).

(Roland is also a composite of sorts of my parents’ fandoms in his likenesses to Stephen King–my mother being a self-professed “avid fan” of King’s–and to Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name from my father’s favorite movie The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly [1966].)

The narrative need for dead mothers ironically underscores their critical role by way of their erasure: their absence inherently constitutes a conflict. But they’ve been erased so often by this point it’s easy to forget this. T.S. Eliot said “kill your darlings”; Disney and King would say: kill your mothers. But that doesn’t mean we should listen.

-SCR